Growing Resilience through Resourceful States of Mind – first published in BACP Journal

Growing Resilience through Resourceful States of Mind – first published in BACP Journal

Case study research explores the potential for growth and change in children experiencing learning and/or emotional and behavioural difficulties when they learn to create their own personal “Welfare State”

In recent years there has been an upsurge of interest and concern in relation to children’s emotional and mental health. Media stories about bullying in schools, excluded children, disaffected youths creating mayhem in their communities, concerns about child pornography and the safety of the internet – all have been presented in the nation’s living rooms, and whether we judge the publicity good or bad, it is now important to recognise that the well being of our children is of widespread interest and concern. A recent government report, “Promoting Children’s Mental Health within Early Years and School Settings” (DfES[i]: 2001) states that “the mental health of children is everyone’s business”, and that adult society as a whole needs to recognise the importance of children’s mental health and emotional literacy. Self-esteem, a sense of identity, strong family relationships and good communications with teachers and peer groups are widely acknowledged as key elements in children who are resilient, and the risk factors for mental ill-health increase with every element missing from the list of desirable conditions.

Being Resourceful

You might be wondering just what is a resourceful state of mind, and how is it relevant to counselling and working with children, and so I’d like to begin by defining the word resourceful:

Webster’s dictionary states: “resourceful” “Able to act effectively, or imaginatively, especially in difficult situations” [ii]

The Oxford English Dictionary defines thus:

“Resources”, “A stock or reserve on which one can draw when necessary”, “An action or a procedure to which one may have recourse in a difficulty or emergency”.

“Resourceful” “Full of resource”, “Rich or abounding in resources” OED, 1979 [iii]

“having inner resources, adroit or imaginative”; “someone who is resourceful is capable of dealing with difficult situations”; Wordnet, 1997, Princeton University.[iv]

As described above, the qualities of being resourceful would be beneficial for all of us, and especially for our children, increasing their resilience as they learn to deal with a modern life fraught with many potential pitfalls and anxieties. Although there are some people who appear to be naturally gifted with a consummate ability to respond appropriately to life’s challenges, it seems that coping with difficult situations with grace and elegance, for at least some of the time, is a skill which may be learned at any age or stage. Clients who present themselves, (or are “sent”), for counselling are unlikely to be demonstrating resourcefulness in the parts of their lives which are causing trouble, since if they were coping effectively with difficult situations, they wouldn’t be clients in the first place. This applies to adults as well as children, but it is particularly relevant to a child, as generally they have less control over their environment, and little if any choice in how they are dealt with when things are not going well. They are required by law to attend school, where they may be experiencing difficulties, and they cannot usually leave their home and family, if that is a source of challenge for them. The demise of the extended family in Western culture has led to children’s support networks diminishing, and with the breakdown of family life and increasing single- parent families, their contact with elders as role models has reduced. Less able to use their resources to change the external situation, it is therefore useful for a child to be able to control their own inner world, to be more resilient, and gain mastery of more effective ways of dealing with external stimuli which may provoke undesirable behaviours. Creating a resourceful state, a “personal welfare state” may be a means of achieving that ability to exercise self-control, gain a sense of self-worth and remain in mental good health.

Resourceful States of Mind

A resourceful state of mind is perhaps best described as a personal inner retreat, a safe platform from which to move forward and explore responses rather than react on impulse. The client can be facilitated in creating this state, using existing inner resources, elicited by sensory-based techniques such as visualisation. It is accessed by the client’s recalling positive experiences, and creating, initially with guidance from the therapist, then independently, their own representation of the moment they have chosen. As a first step, some carefully chosen exercises and games are introduced which will guarantee the client has a recent positive experience of success on which to draw, should it prove challenging for them to remember any other suitable event. The process for creating a resourceful state will vary from client to client, according to their needs. It will include specially designed breathing and posture exercises, visualisation, sounds and feelings, (depending on the client’s preferences) and adjustment of the image by the client to make the strongest possible representation of their chosen moment. This is followed by cultivation of the child’s sensory perception, and contextual rehearsal and role play in situations which have proved challenging in the past. An important factor for the therapist is the development of keen observational skills in noting specific physical responses and their congruence with spoken expressions, and the ability to identify preferred senses and styles of communication in the client, and match them where appropriate.

With practice, resourceful state can become part of a person’s repertoire of voluntarily chosen but unconsciously achieved behaviour, such as riding a bicycle or driving a car, to be accessed and utilised by choice whenever required. When they know and understand themselves better they have a wider range of choices available in how to respond to themselves and to their environment. They can literally become more resourceful in their way of being.

Resourceful states of mind, then, are based on an ability to reflect on and in action, to operate from a chosen response rather than an impulse, and to have an inner mental sanctum, a reserve of strength to draw on when needed. Being able to reconnect to a positive and powerful experience can give confidence and build self-esteem, empowering a client to believe in himself and in his potential.

My fascination with, and, dare I say, passion for resourceful states of mind stemmed initially from a strong personal interest when a young family member had coaching in learning skills about 10 years ago, and was taught to create a personal resourceful state. The subsequent increase in confidence, self-esteem and performance was dramatic, and prompted me to discover more about state management. I researched widely, and found references to “flow” (Csiksezentmihalyi) [v], a state which athletes and performers use in preparation for and during performance, “peak experience” (Maslow) [vi], involuntary ecstatic states which can have transformational effects on those experiencing them, “plateau experience” (Maslow) [vii] which is a milder version of the peak experience, with a more voluntary element, “vital moments” (Goud) [viii] and “mindfulness” [ix], all of which bore some resemblance to resourceful states of mind. This is of necessity a brief list of the reading which informed me, although I can say that in all my searches I found no specific reference to resourceful states of mind pertaining to counselling.

The Research Project

I undertook this research for a Master’s Degree in Psychology & Counselling Practice, which required that the topic was grounded in the researcher’s own practice. When planning the project, I was moved by a desire to discover why at certain times, with certain clients, certain interventions (with particular reference to resourceful state) would appear to work more effectively. I believe that by reflecting in and on action, as described by Schön in The Reflective Practitioner, (1991),[x] I was able to examine my own practice and gain invaluable knowledge and know-how of my work, whilst benefiting from personal insights, and most importantly, being extremely sensitised to the expressions and responses of my clients. My personal resourceful state was important in helping me to adopt an observer position when reflecting on my practice, and in enhancing my empathic skills within the therapeutic relationship.

I chose to use a case study in order to pay close attention to the unfolding process during a series of counselling sessions with a specific child client. This methodology is particularly suited to a detailed study of phenomena occurring in a practice situation, and the work was carried out subject to all ethical considerations, including consent, confidentiality and non-harming, in accordance with BACP guidelines and under academic and clinical supervision. The initial therapy took place between September 2000 and March 2001. The interviews and analysis took place subsequent to the completion of the therapeutic contract, and further research has since been conducted into additional cases, with group work carried out until July 2002.

The Case Study

The client was a 10 year old boy who was experiencing emotional and behavioural difficulties, with problems such as tantrums and aggression reported both at home and at school, resulting in his schoolwork also being affected. He was referred by his mother, on word of mouth recommendation, and attended for 12 one-hour sessions. I initially saw the mother twice, to discuss the case history from her viewpoint, and then to agree the contractual terms, including the agreement for her to be interviewed subsequent to the completion of the therapy. We established that the outcome most desired by his mother was that the client should be happier, more confident, less angry, have fewer tantrums and be more prepared to engage with his family, teachers and peers. If his schoolwork also improved, then that would be an added bonus. We remained in contact for feedback throughout, as is recommended wherever possible in work with children.

The Assessment

““So, why are you here?” I said to the client.

He was a little reserved, quiet and his eyes were downcast as he responded candidly to my request for his story about why he was attending.

“I’ve been getting into trouble at home and at school”, he replied.

“How do you feel about that?” I asked.

He looked at me and hesitated, chewing his lip. He looked down, at his hands, then looked back at me and said “I get…kind of…I’m sort of angry..and I feel…bad.” He spoke quietly and slowly, body twisting slightly to his right, his hands wringing together, his posture slumped.”

During the assessment, the client’s own account of his behaviour matched closely with that of his mother. He told me that, as a result of coming to counselling, he would like to “feel better and not get so mad” and “do better at Maths and English”.

After the assessment session with the client, I asked him if he was interested in participating in my research, taking utmost care to ensure there was no pressure or obligation. I checked again scrupulously the following week when he enthusiastically agreed. After the end of the 12 sessions of therapy, I conducted two interviews with the client.

The first interview took place within a final 13th “closeout” session, and he was very comfortable throughout. He enjoyed going through the agenda we had followed, and choosing those interventions he felt had been most beneficial. He was also quick to tell me what had been least favoured, (“boring”, to use his words), which I regard as a good indicator of the equal balance of power in our relationship. His willingness to interject and interrupt, offering his thoughts during our interview sessions, left me sure that he felt no constraints in communicating his true feelings to me. The same remarks apply to our second interview, which was taped, and where, on transcription, I was able to identify even more precisely how powerful his contribution was.

The subsequent interview with his mother gave rise to some painful, tearful moments for her. She said she was relieved to have uncovered her feelings, and felt very safe speaking to me. I stayed with her until I was sure she was grounded and calm, and suggested she might like to have her own counsellor. She was definite in her positive assessment of the value of the work I did with her son, and confirmed that she had noticed great changes in him. It was extremely interesting that she told me how she had felt enabled to make changes herself, also. Her observation of her son, and the way he went home and told her about what we did in our sessions, led her to decide that she could alter the way in which she related to him. Their relationship improved as a consequence, and the household was generally much calmer, with better communications.

The Results

In analysing the data in the case study, I noticed the similarity in the perceived changes identified by the client, his mother and myself. Although I had not undertaken an outcome study per se, I knew from my reading about case study research (Yin, 1994[xi]; Stake, 1995[xii]; Silverman, 2000[xiii]; McLeod, 1994[xiv]; Higgins, 1996[xv]) that multiple sources of data are highly regarded as a means of reinforcing validity. Therefore I selected amongst the available material from pre-, during and post- counselling, the behaviour, emotions and attitudes identified by all three participants as being subject to change. Changes were also reported from other members within the family, teachers, both verbally and in writing, and from peers with whom the client’s relationships improved noticeably.

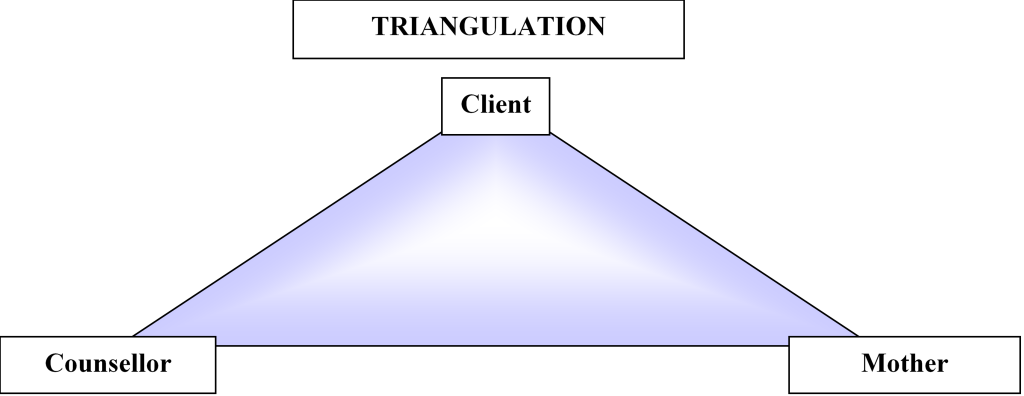

The ABA model shown below illustrates the conditions pre-counselling at A in column one. B represents the changes noticed during counselling. A in column three shows the effects when counselling was discontinued. I regard this information as important because it illustrates triangulation, the convergence of opinion between participants, thus lending credence to the proposition that change did occur.

The ABA model shown below illustrates the conditions pre-counselling at A in column one. B represents the changes noticed during counselling. A in column three shows the effects when counselling was discontinued. I regard this information as important because it illustrates triangulation, the convergence of opinion between participants, thus lending credence to the proposition that change did occur.

Baseline Assessments of Effects of Counselling |

|||

|

|

Pre Counselling |

During Counselling |

Post Counselling |

|

|

A |

B |

A |

|

1 |

Tantrums almost every day |

few tantrums |

few tantrums |

|

2 |

Arguments, alienation |

calm child/household |

calm child/household |

|

3 |

Client self-doubt |

client confidence |

client confidence |

|

4 |

Client impulsive/ thoughtless |

considers decisions |

considers decisions |

|

5 |

Client can’t see outcomes |

foresees outcomes |

foresees outcomes |

|

6 |

Client self-anger |

self acceptance |

self acceptance |

|

7 |

Client sensitivity to comments |

accepts just criticism |

accepts just criticism |

|

8 |

Peer relations tense |

improvement |

improvement |

|

9 |

Bullying |

decreases |

decreases |

|

10 |

School behaviour |

improves |

improves |

|

11 |

Teacher relations |

improves |

improves |

|

12 |

Mother guilt/responsibility |

Mother letting go |

mother letting go |

|

13 |

Mother angry – self |

self accepting |

self accepting |

|

14 |

Mother angry – son |

acceptance |

acceptance |

|

15 |

Mother high expectations |

realism |

realism |

|

16 |

Mother/son tension |

understanding/respect |

understanding/respect |

|

17 |

Disobedience |

explanation |

explanation |

|

18 |

Client/mother don’t talk |

son explains our work |

reminds of principles |

|

19 |

Coping/weakness |

both stronger in self |

both stronger in self |

One of the most effective ways to demonstrate what I discovered about resourceful state in this case is to offer some verbatim quotations from the client.

We explored his experience of resourceful state, and he told me “everything is really calm”, “It’s just silent, and all I can hear is myself”. He had such internal dialogues as “How’re you feeling?” responding with “really happy”, “really sad”, “no emotions”, “every single emotion you can think of”, with the most common emotion being happy. He told me that “it’s calm sometimes and it makes me feel really good when I’m happy and it’s peaceful as well”. The resourceful state was important to him because it helped him “a lot” and “when I’m feeling sad I go into the resourceful state to get over it”, and that he used it mostly “just before I go to school on Monday” and “if I feel really bad on another day then I’ll use it again.”

It appears that the client’s experience of resourceful state supported a wide range of emotions, and that resourceful state might offer the therapeutic potential for the clarification of emerging emotional patterns – exploration and clarification of feelings being a goal of the counselling process. It is also possible that that resourceful state offers the development of emotional regulation skills. The process is not dissimilar to meditation or co-counselling techniques.

The client deliberately accessed the resourceful state when entering stressful environments, whenever he was feeling very sad, or when he wanted to achieve a peaceful, calm and quiet state. The state was also “silent” for him, possibly enabling him to “hear himself”, and providing a quiet retreat away from external influences. It appeared that he had made definite choices in identifying the times when he would use resourceful state, and was also aware of those moments when it would best support him in challenging circumstances.

I asked the following:

Therapist: So what have you learned about yourself?

Client: That I’m very important. I’m not just somebody who walks around everyday doing nothing. I’m really important. That as well.

The foregoing statement is probably an indicator of the client’s self acceptance, that he values himself for what he is, and believes he has worth both to himself and to his world. This might indicate that the conditions for a fully functioning person were present. Satir says that person with high self worth:

“has faith in his own competence. He is able to ask others for help, but he believes he can make his own decisions and is his own best resource.” Satir (1972: p. 22)[xvi]

“This achievement of self-acceptance is usually followed by a sharp increase in the client’s personal power.” Mearns & Thorne (1999: p. 150) [xvii]

Witnessing the achievement of that empowerment and sense of self-worth led me to consider that our therapeutic relationship, with its emphasis on resourceful state, might well have facilitated my young client in accessing his own personal welfare state, a resource from which he will hopefully continue to benefit as he moves through adolescence to young adulthood.

Conclusions

It seems that resourceful state may have provided a resource for the client to experience himself more fully, and that it also allowed him to enter a calm, peaceful frame of mind is highly probable. I propose that his resourceful state offered the client an enabling device from which to operate differently, to consider and choose a response, when faced with the external factors which had previously been provocative to his bouts of anger, frustration and confusion.

The resourceful state appears to help reconnect the client to his sense of self-worth, by enabling him to acknowledge experiences of success, peace, calm or any other feeling which serves to reinforce his ability to regard himself as worthwhile. Sometimes clients cannot remember their successes, they can’t think of anything good they ever were or did. They block their memories of their own competencies, relating only to their perceived failures and lacks. The ability to access a resourceful state of mind, and reconnect to “good feelings” can perhaps help to provide the sense of safety which has been presented by Maslow, Rogers[xviii], Brooks[xix], McGuiness [xx] as crucial to growth and development, and a key feature of resilience.

My continued work with clients, ranging from therapists and older students to children with learning difficulties such as dyslexia and dyspraxia, has reinforced the conclusions I have drawn from my studies, and I am continuing to develop my ideas.

Equally importantly, for myself as a counsellor, working from a personal resourceful state has had a noticeable effect on the development and quality of the therapeutic alliance, and members of my cohort on the MA who were introduced to my work experienced considerable benefits in terms of combating anxiety and stress. As a tool for personal growth, I have been astonished by the simple power a resourceful state holds. Through some very

challenging times of bereavement and loss, I have been able to complete my work, using my resourceful state to facilitate myself in difficult circumstances.

I am currently scheduling Resourceful States in Therapy training workshops from January onwards, for counsellors, teachers and others who work with children, and I am planning to introduce the concept to other groups – such as parents, students and the general personal development market as next year progresses. My book, “Resourceful Intelligence”, based on the research, will be published by Crown House early next year.

For further information, please call contact Christine Miller HERE

[i] Department for Education & Skills (2001, June) Promoting Children’s Mental health in Early Years & School Settings

[ii] Webster’s unabridged dictionary 1996, 1998, MICRA Inc

[iii] OED: (1971) Oxford English Dictionary Oxford University Press

[iv] http://www.cogsci.princeton.edu/cgi-bin/webwn2.0?stage=1&word=resourceful

[v] Csiksezentmihalyi. (1991) Flow: the psychology of optimal experience. New York. Harper & Row.

[vi] Maslow, Abraham H. (1968) Toward a psychology of being (2nd edit) New York: Van Norstrand Reinhold

[vii] Maslow, A.H.. (1976) Religions, Values, & Peak Experiences London; Penguin Arkana

[viii] Goud, Nelson H. (1995, Sept) Vital Moments Journal of Humanistic Education & Development Vol. 34 Issue 1, p24, 11p

[ix] Venerable Henepola Gunaratana. Mindfulness in plain English. URL: http://www.freenet.carleton.ca/dharma/introduction/instructions/sati.html [8th January 2001]

[x] Schön, D. (1991) The Reflective Practitioner; How professionals think in action. Aldershot:Ashgate.

[xi] Yin, R.K. (1989) Case study research: design and methods. London: Sage

[xii] Stake, Robert. ( 1995) The Art of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks, USA. Sage.

[xiii] Silverman, David. (2000) Doing Qualitative Research: A Practical Handbook London: Sage

14 McLeod, J. (1999) Practitioner research in counselling. London: Sage..

[xv] Higgins, Robin. (1996) Approaches to research: a handbook for those writing dissertations. London: Jessica Kingsley

[xvi] Satir, Virginia. (1972) Peoplemaking. London: Souvenir Press.

[xvii] Mearns, Dave; Thorne, Brian. (1999) Person-centred counselling in action. (2nd edit). London: Sage.

[xviii] Rogers, Carl R. (1967) On Becoming a Person; A Therapist’s View of Psychotherapy. London: Constable.

[xix] Coeyman, Marjorie. (2000, November 14th) An eye trained firmly on success. Christian Science Monitor, Vol. 92, Issue 247, p 13, 3pp.

[xx] McGuiness, John. (1993, January) The national curriculum: the manufacture of sow’s ears from best silk. British Journal of Guidance and Counselling, Vol. 21, Issue 1, p 106, 6pp.